The power of conviction

The rider Jan Brink has made dressage known for all Swedes – even those who, beforehand, knew of no other sport than soccer.

It is not only his success on the arena that has made him famous – there have been other performing riders before him. It is his personal story and the small empire he has succeeded building that fascinate.

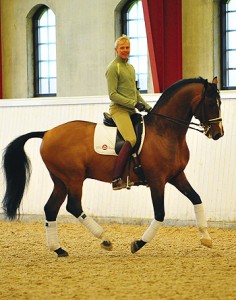

Brink is an exceedingly handsome fellow. I first saw him “live” at Falsterbo Horse Show last summer. He definitely fills the room: tall, slim, elegant – but as he speaks, his strong southern accent and his salty language immediately give him a more earthy quality. And his direct, no-nonsense ways quickly eradicate any sense of mondaine loftiness that could linger from the first visual impression. This is a man who speaks his mind with the conviction of someone who put his hands in the dirt and who knows the realities of life and business.

Then, you see him with the horses. Serious and precise, of course, but also very playful and considerate. You sense a complex character who takes life as it is, the hard aspects as well as the endearing ones.

Many know the story: the child of separated, busy parents, who started out as a junior hockey player but found that the girls were all at the riding school. Whose seriousness on small gigs as a stable lad got him noticed and made his ways upwards, to the state equestrian school and to Grand Prix level of dressage. How he, during his hard work to become a champion, and without any kind of important financial means to begin with, established his own breeding facility and made a name also as a businessman.

“I had no money” he says, “I needed to create a business in order to continue my riding career”. But he also admits that he took a lot of pleasure in building the estate, and that it was important as something to lean back on the times when satisfaction was not reached in competition.

Tullstorp, the stable, is the proof of Brink’s interest in his business. The place, which in the beginning was a small red hut with a farmhouse for cows, has become a full-fledged stud facility where everything is thought out in detail to be practial – but also aesthetic. It is a reflexion of Jan’s sense for beauty, which was also the reason for his choice of discipline. “When I, as a junior, went on jumping competitions, I asked my trainer afterwards if it looked good”, he says. So dressage seemed to be the natural orientation

After four titles as Swedish champion, two Olympic games and one gold medal in the prestigious Aachen dressage cup, Brink has retired from competition, saying that it was one of the best decisions in his life. “You should stop when it is at its best”. He has been thinking a lot himself about what it takes to be a champion – and the answer is : a h… of a lot of things! For Brink, though, the most important factor is work. “You cannot be lazy doing this. It never stops”. He says that there have been promising young riders who have come to his stable for schooling and who have left after only a month. They were simply dismayed to see how much the champion still worked after all the success he had had. “But then you work with your passion”, he says. Indeed, maybe the hardship one is ready to endure for something is the only measure of implication.

Brink’s passion has not been without damage. In the middle of a competition he suddenly lost part of his sight, and a stress diabetes was later diagnosed. But it is evident that for Brink the result was worth the price. Being a champion is, of course, a particular line of work. You are one if you have results. Brink stresses the importance of not getting preoccupied by unsatisfactory phases. “It happens to everyone”, he says, “you often don’t know why, but there is a string of events when things don’t clic. The best thing is to step back, not desperately trying to train more, but outwait the phase”.

Brink gives the impression to have analysed and learnt from every situation. For instance, he seems extremely attentive to other people’s reasoning when talking about business. Maybe because he had to understand the horses’ logic, too. “They can’t be motivated by things in the future”, he says, “they must have a motivating present to feel good and be willing to work for you”.

And whether it is Brink’s sensitivity that has made him exceptionally skilled with horses and business, or whether it is the quadrupeds that have helped him develop that sense, it is certain that working with horses is a very good school of life. Enervment and frustation is never of any use. When you don’t get the reaction you seek, you just have to patiently continue the work, making abstraction of the annoyment in order to advance. This way, after a while, you normally do – with horses and in life.

So, to those who thought equanimity was a boring quality, it could be worth it to think again. After having heard Jan Brink, composure and resilience definitely do not seem out of fashion, and if you have the passion to go with it, the outcome just might be rewarding.